Learn from me, if not by my precepts, at least by my example, how dangerous is the acquirement of knowledge, and how much happier that man is who believes his native town to be the world, than he who aspires to become greater than his nature will allow.

— Victor Frankenstein in Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

Forbidden Knowledge: From Prometheus to Pornography

by Roger Shattuck

St. Martin’s Press, 1996

370 pages

After seeing the atomic bomb explode Einstein is reported to have said, “If I had known, I would have become a watchmaker.”

I do not believe him. Even if he had taken a small office with bright lamps and magnifying glasses to assemble tiny gears and springs into precise timepieces, I think he would have still been consumed by a desire to understand time, light and the universe. Though probably sincere it is impossible to know if Einstein’s hindsight was true. His passion for knowledge destroyed his first marriage and alienated his children; his discoveries provided a foundation for the atomic bomb and atomic power. The General and Specific Theories of Relativity are incredible insights into the nature of the universe and a worldwide nuclear holocaust is a horrific potentiality.

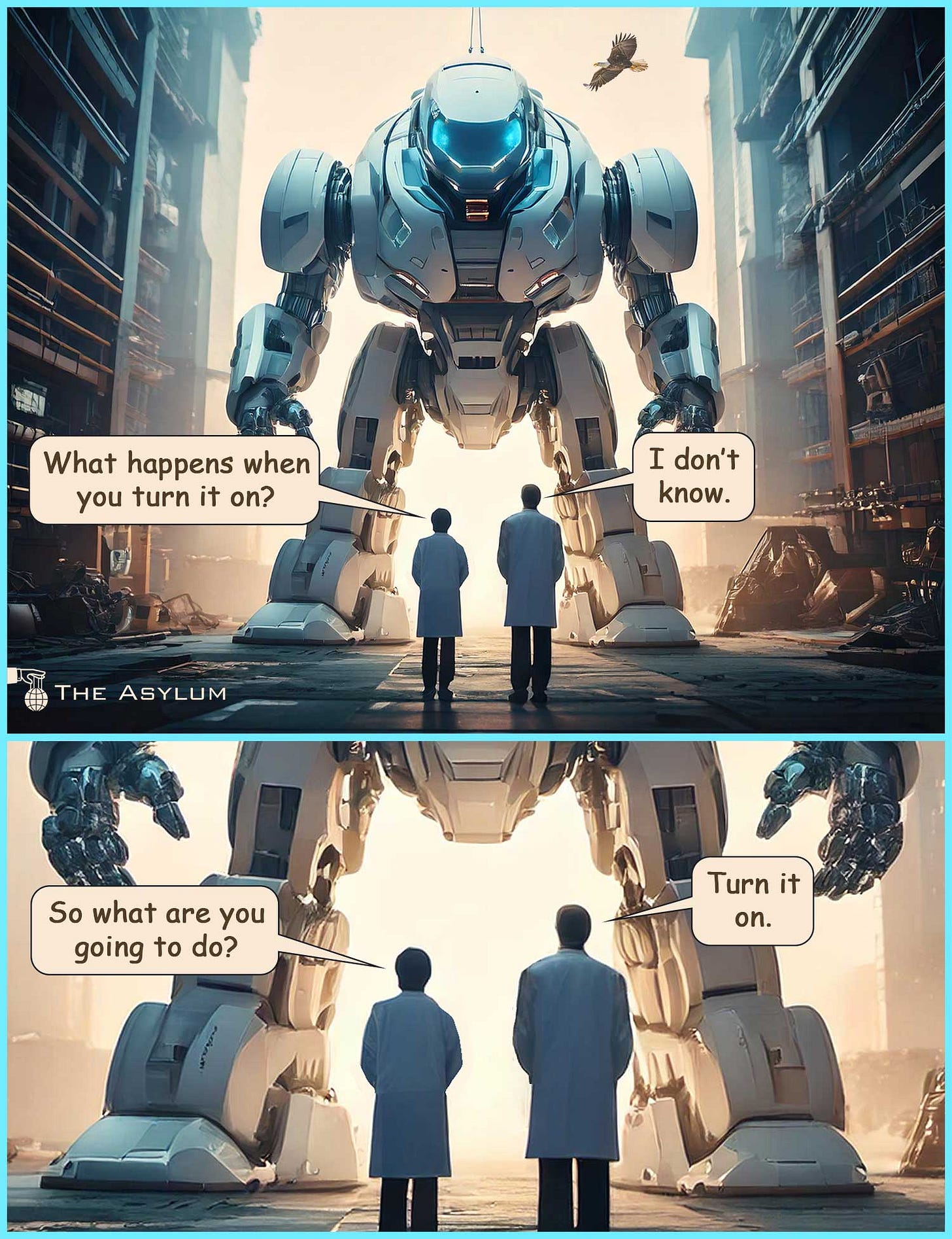

In Forbidden Knowledge Roger Shattuck argues that Western society has accepted, without much argument, that the pursuit of knowledge, regardless of what it is or where it might lead, is innately virtuous. But knowledge, like the human mind, can be used for good or evil. Eden, as it always does, looms in the shadows.

It was Bacon, Shattuck writes, who paved the way for the West’s unchecked pursuit of knowledge for the last four centuries, particularly in the sciences. Shattuck cites the greatest of ancient stories (Adam and Eve, Prometheus and Pandora, Psyche and Cupid, Orpheus, Icarus, Lot) and some more recent ones (Goethe’s Faust, Shelley’s Frankenstein ) to examine the West’s embrace of “unrestricted knowledge and unbridled imagination.”

Six categories of forbidden knowledge are covered:

inaccessible, unattainable knowledge;

knowledge prohibited by divine, religious, moral, or secular authority;

dangerous, destructive, or unwelcome knowledge;

fragile, delicate knowledge;

knowledge double-bound

ambiguous knowledge.

His discussion of all them is engaging, scholarly, understandable and relevant.

Two related ideas form the basis for Shattuck’s assessment of inaccessible knowledge: docta ignorantia and agnosticism. The former he takes from Nicholas of Cusa’s De docta ignorantia (“On Learned Ignorance”) written in 1440. A cardinal, mathematician, scholar, experimental scientist and philosopher, Cusa, like Socrates, believed the truly wise had to be aware of their own ignorance. Man must admit that religious and scientific dogma represent only a shadow of ineffable truth and reality, otherwise a universal certainty drowns faith and stunts further growth and understanding.

Agnosticism comes from T. H. Huxley and Shattuck emphasizes two aspects: our lack of knowledge about ultimate questions and the idea that those questions and their answers are “beyond our reach.” C.S. Lewis wrote,

How many hours are there in a mile? Is yellow square or round? Probably half the questions we ask—half our great theological and metaphysical problems—are like that.

The searching and questioning should continue, but with humility because the greatest mysteries (God and His universe) will forever be beyond comprehension. “A man’s got to know his limitations,” as Clint Eastwood’s character, Harry Callahan, said in Magnum Force. Knowing limitations creates an atmosphere for true awareness and genuine freedom. “The fact that we remain ignorant of how to pose the final questions . . .” writes Shattuck, “should encourage in us an attitude of reverence and wonder toward the world.”

It is, however, “dangerous knowledge” that presents the most difficult problems for society. Central to the book is what Shattuck calls “The Wife of Bath effect” based upon seven words from Chaucer: “Forbede us thyng, and that desiren we.” This is the “forbidden fruit” and Paul’s famous struggle in Romans. Shattuck explains: “We are discontent with our lot, whatever it is, just because it is ours.”

How much curiosity is too much? In science when does the quest for knowledge become so dangerous that it must cease or be slowed down for careful assessment? Shattuck quotes J. Robert Oppenheimer from a lecture he delivered at MIT two years after the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki:

Nor can we forget that these weapons . . . dramatized so mercilessly the inhumanity and evil of modern war. . . . In some sort of crude sense which no vulgarity, no humor, no overstatement can quite extinguish, the physicists have known sin…

Shattuck is not against the pursuit of knowledge, the research and insights of this book make that obvious, but he advises patience and restraint, especially in scientific research, yet, paradoxically (ambiguous knowledge), acknowledges that few people have the necessary discipline to discontinue or limit their pursuits when risks outweigh benefits. He calls the old ideal of “pure research” a “modern myth” because “human agents who pursue that knowledge have never been able to stand apart from or control or prevent its application to our lives.”

Shattuck offers Homer’s Odysseus as a tale of the difficulty of resisting dangerous knowledge, but it also contains a solution to such temptations. Sirens, the half woman and half bird mythical monsters, had the mesmerizing ability with their songs to entice men of the sea to such a degree that they forgot everything and died of hunger. Odysseus traveled to hear them but only after filling the ears of his crew with wax and lashing himself to the mast of his ship.

Odysseus and the Sirens, John William Waterhouse, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

“If we all insist on hearing the Sirens’ song,” writes Shattuck, ”the chances are that many of us will not take the precautions Odysseus did to protect himself and his crew.” These can be in the form of “divine prohibition, or civil laws, or traditional morality, or the inner voice of conscience,” but without them, Shattuck warns, “we sink into selfishness and self-indulgence.”

His account of Ted Bundy is poignant. Bundy, like a young murderer in England, Brady Hindley who tortured, photographed and recorded his victim’s pleas, had read the Marquis de Sade. When Bundy was young he had access to his maternal grandfather’s pornographic collection and acknowledged his penchant for violent pornography. The major media dismissed this information as irrelevant. Shattuck disagrees. He argues that some “temperaments” are unable to process dangerous knowledge without being adversely influenced.

Should Sade be banned? No, says Shattuck, arguing that the question misses the point. Yet, he is appalled that Sade’s work is now so accessible and regarded so highly by the academic world. The more proper question is, “Should we rehabilitate Sade?” Attempts to give Sade the status of a Dostoyevsky or George Eliot “are seriously flawed from a literary and philosophical standpoint,” but Sade “represents forbidden knowledge that we may not forbid. Consequently, we should label his writings carefully: potential poison, polluting to our moral and intellectual environment.” (Shattuck quotes several passages from Sade and warns his readers at both the beginning of the book and in chapter VII that it is not appropriate reading for children or minors.) To believe that environment is the sole cause of man’s behavior is as false as to believe it has no effect.

In Stanislaw Lem’s exceptional novel, Eden, a spacecraft from earth crashes on an alien planet. The crew encounters the planet on several expeditions, but these excursions into the alien world are so beyond human experience the best they can do is theorize and wonder about what actually occurred. After what appears to be an attack from the planet, part of the crew wants to go on another expedition. The Captain says with a smile, “Hardly have the guns ceased to roar than curiosity begins to consume them.” Finally, the ship is repaired and there is a discussion about whether they should leave. Some think they should stay, not only to gather more information, but to help the alien civilization. The engineer disagrees.

It’s a question of the price. Just the price. Undoubtedly we could learn much more, but the cost of obtaining that knowledge…it might be too great. For both sides.

What scientists will lay down their microscopes, forfeiting the fame and money of a great discovery, when it becomes obvious that the risk, either personally or to civilization, outweighs the potential benefits? An enlightened life rests in a precarious place between law and license, patience and carpe diem, promiscuity and abnegation, dogmatism and relativism.

Knowledge can become an obsession, a forbidden pit where life is known, but not lived, where love is expounded, but not practiced, where, Shattuck writes, “curiosity may tempt us away from what is most important: the life that lies immediately in front of us.”

Great review, makes me want to read the book 👍🏼

I couldn't help but get a nagging thought (I've oft had before).

To do what Shattuck suggests, we'd need a clean slate in terms of being enlightened communities, with certainty of intentions of others that if it's decided that certain knowledge is not pursued, no one will pursue it elsewhere, without the possibility of secret pursuits. Because history rhymes and human desire for power (and fame and riches), unless there is a global level community of sorts, it's not practical.

And this is the crux of it.

Just as we shouldn't ban books or ideas, the quality of the social fabric necessary to underpin a society mature enough to educate "correctly", and rehabilitate where necessary, is such as to make it seem (to me) unrealistic, given our current circumstances.

I wonder if our current predicament is sort off inevitable, and the science fiction part of me interprets the stories of old slightly differently, and wonders whether this is the first time we've reached this predicament as a species.

Civilizations rise and fall, the debate rages about why etc, but given the magnitude of the destructive potential at hand, I'd say it's possible to think in more macro terms at this time.

I'm not a doomsayer, just that, the ideas of good and evil knowledge, the idea that some things are best left alone and others need individuals to have corrective rehabilitation at hand if the cumulative effects lead them, for instance, towards psychopathy, all this presupposes a mature and extremely powerful enlightened hierarchical structure capable of imposing a will that's not tyrannical or biased by un-virtuous values and ends.

In our current mess, with the culture of state secrets, security agencies, technological ubiquity, a defacto social and economic credit system, a blind allegiance to capitalism and liberalism (that're never accurately defined or described), I just don't see a happy ending without passing through a time of intense suffering (and death).

So very interesting! Thanks for the book review.

A few synchronicities therein (for me): First, I'm getting through ever more of Walter Russell's brilliant (and enigmatic) writing and today I read quite a bit about the differences between true Knowledge, and what we generally consider as scientific knowledge. The first is more or less already within us because it is more or less the same as God, and the second (lower-case "k") knowledge is what scientists find or learn. Russell says that the latter really isn't even knowledge at all, but rather a series of memories. Well, it's a long story and makes more sense in the context of that long story. Plus you have to read it repeatedly, I'm sure, but it was noteworthy simply because of the timing of reading such similar words.

The main synchronicity involves Stanislaw Lem, though. I haven't thought about Lem for a long time -- although you and I might have exchanged a comment, perhaps? -- but quite literally immediately before reading your post, I had responded to someone in a Note who wondered if I had a recommendation or two for sci-fi. One of the authors I recommended was Stanislaw Lem!

The other synchronicity for me was from a previous comment to the same Note where I mentioned Carl Sagan's rather juvenile, but famous "extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence" claim. After wrapping up my comment, I immediately looked at another writer's new post and in the second paragraph or so, he too, mentions Sagan and the same quote (also disparagingly, which makes it even more synchronicity-y)!