Author’s Note: Many readers of The Asylum may not know this site was first a critique of corporate culture back in the late 90s and early 2000s. In honor of Labor Day I offer this book review from around 1999.

The use of leisure is an Art of immense importance in the work-a-day world; for it teaches us what we should do with our time, our own time, when we have any; for our working hours are literally not our “own.”

— Sir Ian Malcolm, The Pursuits of Leisure

a review of

Leisure, the Basis of Culture

by Josef Pieper

Saint Augustine’s Press, 1998

paperback, 160 pages

In Leisure, the Basis of Culture, Josef Pieper confronts the culture of “total work” where people are defined by their jobs to the exclusion of character, where a country’s greatness is based almost solely upon economics—Gross National Product—and leisure is simply time away from work, free-time, your own time, time off the clock, necessary R & R so one can return to the battlefield of labor rested and rejuvenated. Pieper contends that these ideals destroy the opportunity for a meaningful life.

What is the culture of “total work?” The “worker,” and Pieper uses this term in a philosophical, all encompassing sense, is not only or solely an employee but rather anyone, employed or not, who has accepted, whether consciously or not, the ideals and tenets of a world consumed by work: “work as activity, work as effort, work as social function.” Work defines meaning. What do you do? How much do you make? These questions take precedence over and/or replace philosophical and religious queries: Who are you? What is the meaning of life? Is there a God?

For the “worker” activity is meaningful: as long as “workers” are active, as long as they accomplish something then they have succeeded. This idea is reflected in our culture of “busyness (business)” in the often asked Monday morning question: “What did you do this weekend?” The activity of the workweek rarely ends during the weekend. There are errands to run, chores to do and the need to engage in recreation. “So . . . how was your weekend?” “Busy,” is the answer often given. “I came back to work to relax.”

“We make money the old-fashioned way,” said the commercial, “we earn it.” Nothing of any importance, says the world of work, comes about without effort. The self-made man earned his position, his money, his power. To consider any other possibility detracts from the accomplishment, belittles the man. Luck, like money, comes from the sweat of the brow and if you have more of either than others it is only because you work harder than they do. Pieper writes, “The innermost meaning of this over-emphasis on effort appears to be this: that man mistrusts everything that is without effort; that in good conscience he can own only what he himself has reached through painful effort; that he refuses to let himself be given anything.” Ironically the Western worker, raised in a culture dominated by Christianity, has been immersed in the religious concept of grace and yet is unable or unwilling to transfer it to the corporate world. “God helps them who help themselves,” which is not in the Bible, rolls off their lips more frequently than something that is: “It is vain for you to rise up early, to retire late, to eat the bread of painful labors, for He gives to his beloved even in his sleep.” Few “successful” people want to admit that their positions are not a direct result of their effort.

“Workers” become “functionaries” of the “total-working state.” Meaning is anchored to the “worker’s” material contribution to their country, made possible by their activity and effort, or in a less universal way to their corporation, business, church or family. The latter used to entail one “provider,” but the two-income home has also become the three, four and five everything-else one: three-television, three-car, three-phone, four-bath, five-bedroom and all for the sake of the family. Clearly, however, something is missing and that something, Pieper argues with reason, passion and persuasiveness, is leisure. This is a superb book, extremely relevant for today and more timely than it was 50 years ago when it was first published.

Pieper is not against work per se, not opposed to the world of business and economics. These are, of course, he argues, extremely necessary. Without work leisure and philosophizing would not be possible. What Pieper is against is the “overemphasis on the world of work” and the extent to which the philosophy of “work-for-work’s-sake” has invaded and for all practical purposes taken over Western culture. “For that the world of the ‘Worker’ is pushing into history with a monstrous momentum,” writes Pieper, “. . . of that, there can be no doubt.” The question for Pieper and his readers is this: “Can human existence be fulfilled in being exclusively a work-a-day existence?”

Leisure is not simply time away from work. Any time that is necessary in order to recover from work, whether it be breaks, vacations, weekends or free time, is an extension of the work day and as much a part of work as the labor put in while one is “on-the-clock” or “at the office.” Leisure is time beyond this. “Workers” must escape work and “step beyond the working world and win contact with those superhuman, life-giving forces . . .” Pieper explains that the ancients had no word for work. Aristotle wrote, “We are not-at-leisure in order to be-at-leisure.” The reason to work, in Aristotle’s view, is not to obtain money, position of power, but rather to secure leisure.

According to Pieper three things make leisure possible: the “building up of property from wages, limiting the power of the state, and overcoming internal poverty.”

When people are poor most, if not all, of their time is consumed by the constant quest for the necessities of life. Ironically, this quest is often the self-imposed plight of the middle class and beyond. “For my part,” wrote Bertrand Russell, “the thing that I should wish to obtain from money would be leisure with security. But what the typical modern man desires to get with it is more money . . .” Instead of living a financially comfortable existence when a higher paying job or an inheritance comes along many people choose to burden themselves with larger financial responsibilities in the hope that the new house, the extra car or the European vacation will fill the void or at least keep them from thinking about it.

If economic poverty can be overcome there may still be the problem of the state. Pieper knew this problem well: he was a German writing in 1947. When the state is too powerful it demands that all the efforts of its citizens be involved in the “servile arts,” that is those occupations that are utilitarian, that contribute to the state in a measurable way. The “liberal arts,” the specific realm of leisure, are viewed as impractical or unnecessary and are justified in the eyes of the state only if they further its aims. Hence, poetry or the theater or literature are used only as propaganda, not as a means to pursue truth or to object to the prevailing ideology of the day.

This is why it is extremely necessary to overcome “internal poverty.” “[T]he total-working state,” writes Pieper, “needs the spiritually impoverished functionary, while such a person is inclined to see and embrace an ideal of a fulfilled life in the total ‘use’ made of his ‘services.'” It is not, however, enough to be only a spoke in the economic wheel, yet many people look for fulfillment in the world of work “till in snatching at these lesser gifts,” wrote Alexis de Touqueville in Democracy in America, they “lose sight of those more precious possessions which constitute the glory and the greatness of mankind.” The one who has overcome internal poverty is able to discern and fight against the propaganda of the state and of the ideology of the “worker.” The real tragedy of the spiritually impoverished is their inability to recognize their own situation. Marx, according to Dennis Dalton, saw that impoverishment in both the proletariat and the bourgeoisie, the former degraded by constant work to obtain necessities, the latter unaware that the pursuit of money had conquered their souls.

What is leisure? What activities constitute a life of leisure? “[I]n leisure,” Pieper writes, “man overcomes the working world of the work-day not through his uttermost exertion, but as in withdrawal from such exertion.” The working world is about utility, about effort, about practicality, about efficiency, about the “bottom-line.” “It could be said,” Pieper writes, “that the heart of leisure consists in ‘festival.’ In festival, or celebration, all three conceptual elements come together as one: the relaxation, the effortlessness, the ascendancy of ‘being at leisure’ . . . over mere function.”

The effortlessness and relaxation of leisure are not the same thing as idleness. Pieper argues that idleness is the root cause of the overemphasis on work. Idleness is what produces the workaholic. The ancient word for it, acedia, carried with it the idea that people are not at one with themselves, that regardless of their “energetic activity” they are not at peace. “Acedia,” Pieper writes, “is the ‘despair of weakness,’ of which Kierkegaard said, that it consists in someone ‘despairingly’ not wanting ‘to be oneself.'” From idleness, then, springs “Restlessness and Inability-for-Leisure . . .” Erich Fromm once asked the question: “Could it be that the middle-class life of prosperity, while satisfying our material needs leaves us with a feeling of intense boredom, and that suicide and alcoholism are pathological ways of escape from this boredom?”

It becomes clear in the second essay of the book, “The Philosophical Act,” what Pieper considers leisure to be, which is why the second half of the book is so important in completing the first. For Pieper the proper use of leisure is the “philosophical act.”

Wonder is the beginning of philosophy. It is the ability, Pieper writes, “to remove oneself, not from the things of the everyday world, but from the usual meanings,” to be so “astounded by the deeper aspect of the world, [that one] cannot hear the immediate demands of life . . .” The world of work is forgotten in wonder produced by the contemplation of the mystery that is existence. Why is there something and not nothing? Is the universe infinite in time and space? “[T]he sense of wonder is . . . the sense that the world is a deeper, wider, more mysterious thing than appeared to the day-to-day understanding.” This kind of wonder can be and should be unsettling. It disturbs people because things that once were so sure to them, so self-explanatory may suddenly be a mystery, be unexplainable. They used to know something and now they do not. “But this un-knowing,” Pieper writes, “is not the kind that brings resignation. The one who wonders is one who sets out on a journey, and . . . persists in searching.”

Initially leisure must be secured in practical ways: financial security, time beyond the world of work and an escape from “internal poverty.” There is a bit of a paradox here. Leisure, properly engaged in, will eradicate internal poverty, but the internally impoverished will have a difficult time with leisure. The trouble comes because the work-a-day world instills habits into the worker that are opposed to leisure: activity for the sake of activity, perpetual restlessness–the idea that there is always something one should be doing–materialism and self-reliance to a fault. Leisure embodies calmness and patience. One is unrushed and waits for good with a healthy detachment–unworried. One is not inactive–but one’s activity is not agitated. The book does not have to be finished in a week and garden projects may linger for months. What is important is that we are mindful of the reality around and within us and that this mindfulness instills in us a sense of wonder: the world is seen for what it is and we truly begin our awareness of both its beauty and its horror.

Life may be bearable living solely as a functionary, as the ideal “worker” of the utilitarian world of business or as “the proletarian . . . whose life is fully satisfied by the working-process itself because this space has been shrunken from within,” but leisure imbues it with profound satisfaction. “For it is in leisure genuinely understood,” Pieper writes, “that man rises above the level of a thing to be used and enters the realm where he can be at home with the potentialities of his own nature, where, with no concern for doing, no ties to the immediate, the particular, and the practical, he can attend to the love of wisdom, can begin leading a truly human life.”

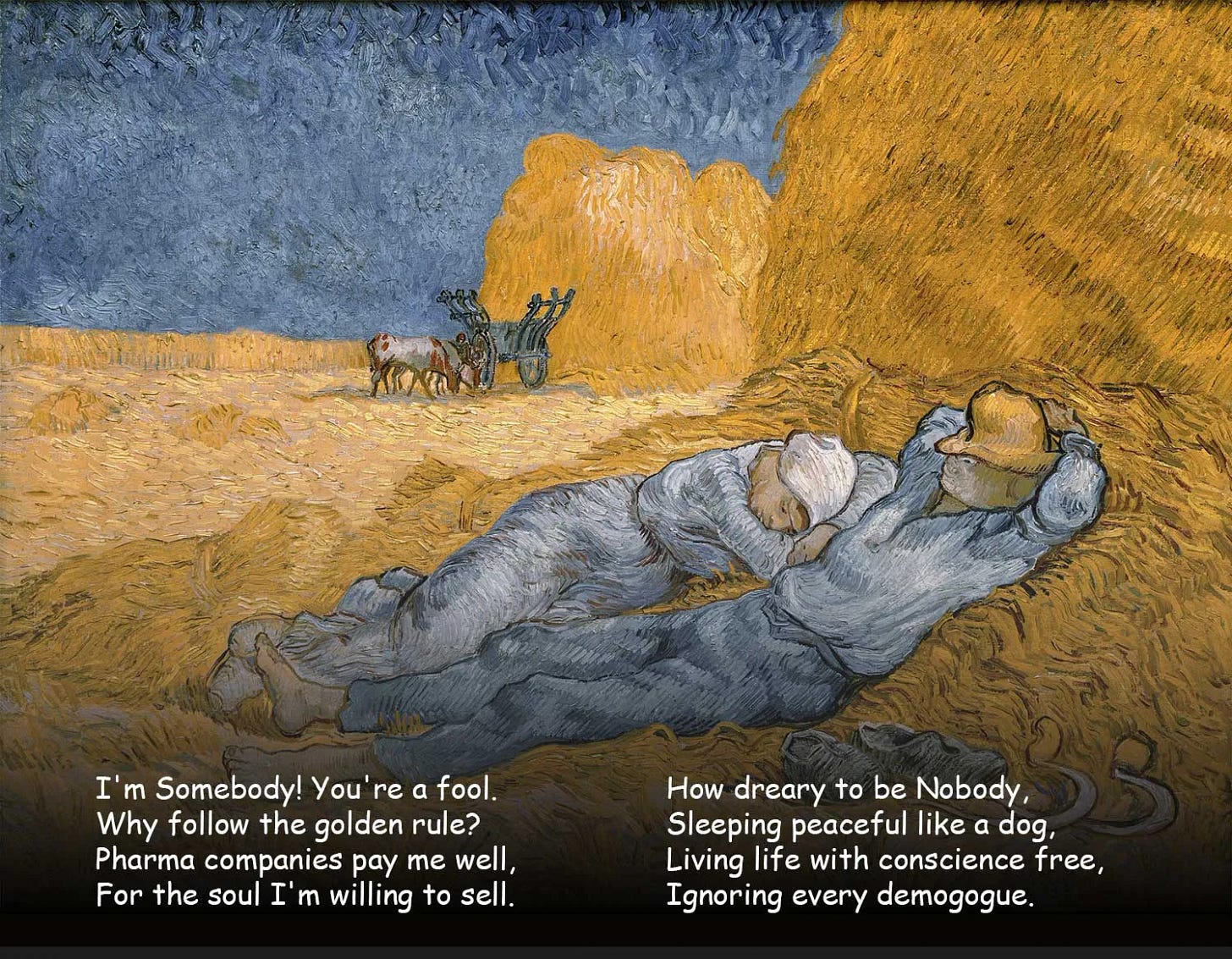

Noon — Rest from Work (After Millet) by Vincent van Gogh, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons (poem by The Inmate)

Works cited:

Dalton, Dennis, from the lecture “Marx’s Vision of Political Economy,” tape #5 in Power Over People: Classic and Modern Political Theory, Superstar Teachers: Great College Course Lectures, produced by The Teaching Company in cooperation with The Resident Associate Program Smithsonian Institution.

Fromm, Erich, The Sane Society, Rinehart & Company, Inc., New York, N.Y., 1955, pg. 10.

Malcolm, Sir Ian, The Pursuits of Leisure, Books for Libraries Press, Freeport, New York, 1968, pg. 1.

Pieper, Josef, Leisure, the Basis of Culture, translated by Gerald Malsbary, St. Augustine’s Press, South Bend Indiana, 1998.

Russell, Bertrand, The Conquest of Happiness, Liveright Publishing Corporation, New York, N.Y., 1971.

Touqueville, Alexis de, Democracy in America, translated by Henry Reeve, revised by Francis Bowen, Edited and abridged by Richard D. Heffner, A Mentor Book, New American Library, 1984, pg. 213.

Excellent review!

He not only assumes the gender, but he also calls the individual "trash", instead of a sanitation systems engineer being exploited this evil, rich white boomer!

I know because corporate media whores told me so.